It’s been a while, but I’ve been concentrating on picking up the pieces of an interrupted life. It’s taking longer than anticipated.

I started this blog as a way to share my work as a writer in the Middle East and some experiences of expat life. But cancer scuppered the work, the Middle East and the expat life. Very cross about this, I decided that I could practise my grammar skills and keep my hand in with the writing by blogging about the C-experience when the mood did grab me. It mildly amused me that it had come to this: one day I’m efficiently writing guidebooks and editing others’ features, the next I can barely string a sentence together.

To write a blog, to put it out there, takes a leap of faith. You’re writing blind to an invisible audience – or possibly no audience. Unlike being commissioned to write a feature or a travel guide, when the publisher is interested in what you write and, even better, pays you (yay!) with a blog you hope (or pray), that you’re not making an utter fool of yourself and that someone, somewhere, might actually want to read your uninvited thoughts and opinions about something intensely personal. I cringed when I published my first cancer post because I thought it was quite arrogant to imagine that anyone, apart from a few close friends might be interested in me spilling my guts, (and anyway I’d emailed them personally). On the other hand, I had been absent from twitter for a while and it was a conveniently detached way of letting my gaggle of followers know the reason why.

Feedback was positive, support gives you a warm glow, but if I’m honest, the real reason I blogged when I had cancer was for me. To remind myself that I still had a skill. That I could still do something. My career as a writer took off in 2006 when I moved to the Middle East. When I got cancer, seven years later, I had to return to the UK and leave it all behind. A year of treatment, another for recuperation, my career had to be shelved. Writing the blog was the one thing I could do that reminded me that I was still a writer.

But two years on from diagnosis, and upon receipt of my annual all clear last November, I guess it’s time to update the blog and focus on life now. To my surprise I discovered that I’d penned twenty-one blogs, but had only posted half of them. Some were too honest and some were too personal. The rest were amalgamated into newer versions as weeks passed before I could muster up the enthusiasm to complete them.

Here’s a tiny one I wrote a year ago:

Power to the Untidy Brain: “Perspective is a skew-whiff thing. I am feeling down at the thought of returning to our home in St Albans – back to the life of seven years earlier, back to normality, to reality, to mundane humdrum and routine. Then that perspective rolls into another one: Dubai: a flat landscape in all senses – mono-climatic, sun and heat; LEGOLAND backdrop and the ‘hood where we dog-walked; school run, Dubai International Financial Centre and my office, work, my small group of friends there. Suddenly that perspective rolls into the house in St Albans, space, potential, new beginnings, writing, my novel, open doors. And that perspective rolls into restrictions, the school run, my treatment, feeling crap, compromise, loneliness, winter nights. Which rolls into four months along the line, the idea of a new job, planning for the future, my book, getting fit and well…. The image I have in my head is of those 10-sided, thick-walled Luminarc drinking glasses, rolled on their side, pouring perspective, like liquid, sand or pebbles, onto the next narrow plane in a continuous cycle. That is my perspective.”

I liked this a lot when I re-read it. Yet I despair a little, because it still applies to my state of mind, from one day to the next and one week to the next. And that is frustrating, because two years on from the end of treatment I thought life would be back to normal, all sorted.

But, it appears that Life After Repatriating Due To Emergency is not like a piece of elastic. It does not just ping back to how it was before. Like my body, it’s a new shape, and not, if I’m honest, one I’m totally happy with. Obviously I’m totally happy that I’m cured. That goes without saying. But – and there is one – when you have to walk away from everything that represents your life (on top of the major health scare), the process of adjustment isn’t snap, crackle and pop rapid.

One Sunday morning in May, two years ago, a normal weekday out in the Middle East, I got up early, got dressed, had a coffee, and said goodbye to my daughters, then aged ten and seventeen, and my dog, (my husband had had to leave earlier to go to work in Qatar). They would have to get ready for school in a short while, but I took a taxi to the airport, where I mingled with the holidaymakers and business people. I sat through my flight numbing out to film after film. I was met by my parents, seven hours later. That night I slept in my childhood bedroom, in the house I’d left when I was eighteen. The following morning, I took the Tube into London and embarked upon a year’s worth of treatment to get rid of breast cancer. I would not see my girls for another month. I never saw my home, my work, my friends and my life of seven years again.

I could not dwell on it. I could not grieve. I could not cry. If I had even thought about it for a second, I would have come apart. I took my doctors’ advice and focused very hard on one hour at a time.

My son who was already in the UK at university spent occasional weekends with me. My daughters and husband visited me for a weekend, a month after I arrived. But one daughter still had to complete AS levels, the other her SATs. They returned to Dubai for one more month, before leaving for good. My husband couldn’t return permanently for another five months.

My daughters joining me, was the most uplifting thing that could have happened. We got dressed up, we did our makeup, we watched films, we went out for meals. They made me laugh and cuddled me when I was upset. And my role as an adult was re-established again. My parents struggled. Yes, with me being ill. But more with the disruption that comes with (unwanted) houseguests. They’d had a full and busy life and now they were having to play nanny to a sickly daughter and two bewildered granddaughters. Within a month of my arrival, they had asked me when I was going to be leaving. When their granddaughters arrived, they gave me a deadline. Although my own house would not be tenant-free until September, they wanted us out end of June. There was no room for us, and no room for negotiation.

I paced around in my childhood bedroom, by this time bald, by this time, overwhelmed by the surreal situation I had found myself in – the very rapid deterioration of a relationship with my parents, buoyed up only by the relentless positivity of my two amazing daughters. Disorientated and feeling very alone, I was too embarrassed to call my (very good) friends for help. I couldn’t expect them to drop everything, when I’d only been back in the UK for two months after so long away and they were all getting on with their own lives. It occurred to me that this is how victims of abuse might feel when they can’t admit to what is happening to them and can’t actually believe that something like this is happening to someone like them. I scrolled through contacts on my phone, trying to pluck up the courage to call someone to ask them if we could stay with them until we could get a rental property sorted out. And then when I could finally breathe again, I remembered that more than one had actually offered me a place to stay – knowing that things were tricky for me. I should not have doubted my friends – they were phenomenal in their support. And one bonus of the chemotherapy: it did suppress my emotions, so I felt nearly nothing.

This is not a woe is me story, or a blame tale, but, an explanation as to why it’s taking me so long to pull through. And why it’s still the subject of my blog. For a year I focused on nothing but my treatment. When it was done, there was time to think. I acknowledged, then had to deal with, the trauma of abandoning my home, my life; of having cancer when I’d always been so fit and healthy; and of recognising that blood is not always thicker than water. The reflection in the mirror was a daily reminder of what I’d been through, and the fear and anxiety, like an unhelpful muscle memory, were indelibly ingrained in my psyche.

It took a time to mourn these things. I suspect I was depressed. I cried. A lot. I had my first annual check up last November. A mammogram, an ultrasound and an MRI scan, contributed to a flashback of the dry-mouthed-fear variety, akin to how I felt when first diagnosed. I got the all clear. I cautiously breathed easy again. Anxiety was nudged, reluctantly, to the back row. I did not want it to consume me anymore. I started to enjoy socialising with more than a mere handful of closest friends. I rediscovered a semblance of the gutsiness I used to have when I lived abroad – that allowed me to do things I wouldn’t normally do, to climb out of my comfort zone, to be whatever I wanted to be. It was, I realised, time to jiggle that Luminarc glass round a bit.

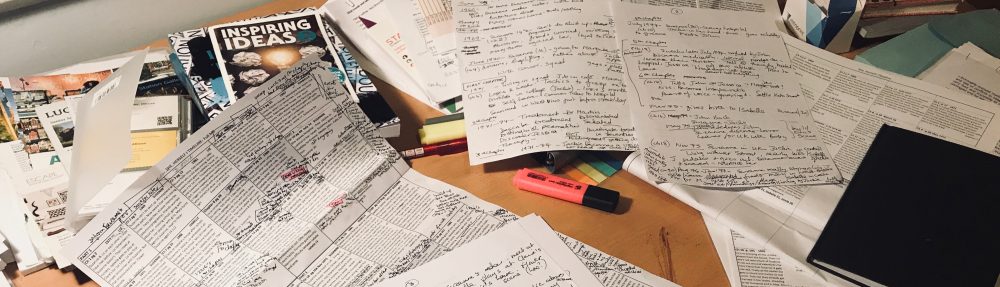

On the one hand, I missed, more than anything, my work and my fellow writers. On the other I did not want any stress. I needed a solution. I joined a Writers’ Group and met lots of writers. I volunteered to help organise their Writers’ Conference so that I could flex my professional muscles. I gave the manuscript of my novel to a group of Beta Readers and started the edits based on their feedback. I plucked up courage to read chapters to my Writers’ Group, which is galvanising me to make the final changes.

The Tamoxifen I take gives annoying side effects, but I don’t dwell on them so much now. I don’t like my new shape as much as the old, so I’ve joined a different sports club and committed to classes I enjoy. I slather on the makeup and buy new clothes when I feel like a boost. The hair is finally approaching a tenuous bob. The reflection I see in the mirror is starting to resemble me.

There has been no great epiphany. I’m still searching for the root of true happiness and the miracle cure for anxiety disorders. I am not yet bursting into song and climbing every mountain. But, most of the time, that Luminarc glass is half full. And if omens and spiritualism are your thing, you’ll like the fact that two deer recently leapt out of the forest I was driving through, in front of my car, narrowly avoiding becoming venison. I just thought it was my lucky day and a great experience. But others told me it had a meaning, so I did a bit of research, and this is what I found:

When Deer cross your Path it means:

– Trust your instincts

– Be kind to yourself

– Remove yourself from negative influences

– Embrace the lure of new adventures

No one else saw the deer. Only me. I think I’ll take it as a sign. I think I’ll journey on!